Comic moments in life are an essential antidote to tragic events unfolding relentlessly around us. Recalling such serendipitous moments also lightens a heart that may weigh heavy from life’s challenges. That is why a smile brightens my face just in telling you about the showdown, in miniature, on my front stoop one sunny afternoon between a grass snake and a praying mantis.

Comic moments in life are an essential antidote to tragic events unfolding relentlessly around us. Recalling such serendipitous moments also lightens a heart that may weigh heavy from life’s challenges. That is why a smile brightens my face just in telling you about the showdown, in miniature, on my front stoop one sunny afternoon between a grass snake and a praying mantis.

It was fascinating to watch, as I came full stop a few feet away. A tiny praying mantis was poised, eye-ball to eye-ball, with the much larger snake for what seemed like a long time. I figured the former would be a nice appetizer for the latter. But, who would think? The praying mantis merely jerked its head forward threateningly, and the snake backed off, slithering off my stoop into the garden.

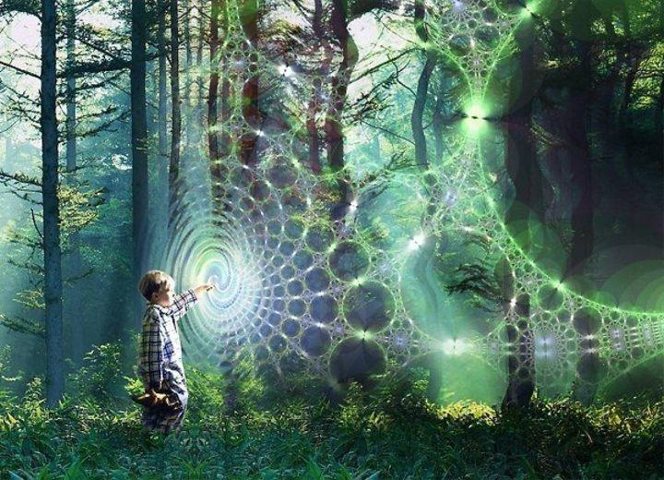

Bearing witness to the wonders of Nature is a delightful practice to relax the mind. Doing so also exercises our higher qualities, such as patience and being present in the moment, that help us become more fully developed as human beings. That is why the credo to “slow down and smell the flowers” truly is not a frivolous piece of advice but, on the contrary, a piece of wisdom to take to heart. Even your brain will thank you.

Deeply gratifying is to have the wisdom of my own quest for inner and outer balance in recent years verified by the scientific evidence presented in The Shallows, What the Internet is Doing to Our Brains (2011) by Nicholas Carr. A Pulitzer Prize Finalist, this book’s importance also is evident in reviews such as Slate magazine Michael Agger’s referral to it as nothing less than “Silent Spring for the literary mind.”

Indeed, the technologies upon which we have come to rely are filled with paradox. Not for the first time do I find myself ambivalent in writing a blog that will entice readers to concentrate their gaze, and stay engaged long enough to read through my philosophical musings. In doing so, my hope is to inspire thoughtful reflection.

At times, however, I want to implore you to turn off whatever computer, iPad, smart phone or other gadget into which you have plugged your mind. Leave the techie toys at home or the office, find a park or a wood or a beach, and linger for a while. Open your mind and soul to the ambience of a natural environment.

Tune in to your body, physical senses and feelings, through visceral interactions in real time and real space. Allow the poetry of your soul to awaken. Discover contemplation.

As for me, I feel blessed to have my computer positioned beside a large picture window that overlooks a wealth of countryside greenery. In these summer days I listen to the birdsong of the barn swallows who come and go frequently to their nest under the eaves above this window, and take delight in bumblebees dancing on the flowers.

Here’s a question to reflect upon. Given the Internet’s ubiquitous presence in our lives, professionally and personally: How are you creating your inner and outer balance?

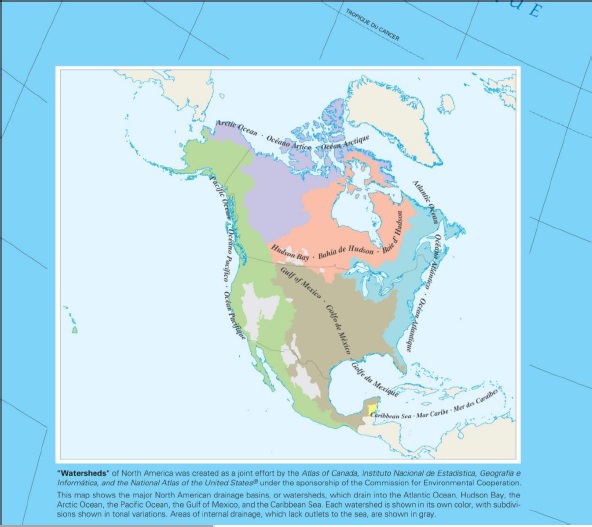

To help us understand better our enchantment with the ever-evolving `intellectual technology’ called the Internet, The Shallows author Nicholas Carr describes the trajectory of a computerized world that began more than a half century ago.

He also confesses to his own enchantment and efforts to negotiate digital tools, so predominant in all our lives, and essential for his livelihood. The impetus to write this book was seeded in his quest to discover what’s been going on inside his own head:

“The deeper I dug into the science of neuroplasticity and the progress of intellectual technology, the clearer it became that the Internet’s import and influence can be judged only when viewed in the fuller context of intellectual history. As revolutionary as it may be, the Net is best understood as the latest in a long series of tools that have helped mold the human mind” [Carr, 2011, p. 115].

and the progress of intellectual technology, the clearer it became that the Internet’s import and influence can be judged only when viewed in the fuller context of intellectual history. As revolutionary as it may be, the Net is best understood as the latest in a long series of tools that have helped mold the human mind” [Carr, 2011, p. 115].

Nicholas Carr is a fabulous storyteller. His book can appeal to an audience wide and diverse, as he walks us through centuries as far back as ancient Greece, ranging from the thoughts of Socrates to the thoughts and “feelings” of supercomputer Hal, a key character in Stanley Kubrick’s prophetic sci-fi film 2001: A Space Odyssey.

In other words, Carr relates history through the disparate personalities of major thinkers and creators, showing how and why particular choices happened, up to and including Hal’s disquieting symbolic role, which is to provoke us to pay attention to who and what we are becoming, as human beings, through our particular choices.

The yin-yang of Carr’s storytelling style is quite brilliant. On the one hand, he delves into the minutiae of tiny details in the lives of historic personalities, in regard to how they variously grumbled, yet coped with, technological changes in their respective eras.

On the other hand, Carr presents the breadth of conflicting views on the multi-layered benefits vis à vis the pitfalls. In the best tradition of good journalism, he equips the reader to make up his or her own mind, more fully aware in negotiating daily sojourns onto the Internet, known to us intimately as `the Net’ or `the Web.’

The Shallows‘ ultimate purpose, regardless, is to take us on a journey that helps us be more receptive to what the latest science now can tell us, about the Internet’s impact on our brains as individuals, and collectively, as societal cultures.

Carr characterizes, metaphorically, how online searches and search engines’ pathways fleetingly direct our attention to “snippets of text…while providing little incentive for taking in the [written] work as a whole. We don’t see the forest when we search the Web. We don’t even see the trees. We see twigs and leaves” [p. 91].

Consider what Carr suggests above. If I sprinkled my usual array of hyperlinks through this post, would you be bouncing out and hopping all over the Internet like an `energizer bunny,’ maybe or maybe not hopping back to finish reading this post, grazing on small, disconnected morsels of information, back and forth?

My intention, when I do insert hyperlinks, is not to please Google but, much more importantly, to provide deeper and more expansive understanding to my readers. My assumption has been that folks would read through my whole post and, only then, might follow up – to learn more – by checking out the content in my offered hyperlinks.

But, regrettably, according to Carr, uninterrupted linear reading of a narrative is being replaced, increasingly, by an online reading habit that merely scans a page and is very attracted to any distraction such as hyperlinks. Oh dear.

The author declares: “The news is even more disturbing than I had suspected. dozens of studies by psychologists, neurobiologists, educators, and Web designers point to the same conclusion: when we go online we enter an environment that promotes cursory reading, hurried and distracted thinking, and superficial learning” [p. 115-16].

In his chapter “The Church of Google,” Carr outlines Google co-founder Larry Page’s view that the human brain does not just act like a computer – a popular notion that Carr challenges – but instead is a computer, “an extreme view,” says Carr. He expounds on how Google’s vision largely is based on Page’s vision, a vision influenced by Page’s father, one of the pioneers of artificial intelligence.

In his chapter “The Church of Google,” Carr outlines Google co-founder Larry Page’s view that the human brain does not just act like a computer – a popular notion that Carr challenges – but instead is a computer, “an extreme view,” says Carr. He expounds on how Google’s vision largely is based on Page’s vision, a vision influenced by Page’s father, one of the pioneers of artificial intelligence.

Carr next explains why the `brain as computer’ metaphor is basically incorrect, as a fallacy “built on reductive assumptions.” I urge you to read The Shallows, because my post cannot do justice to the important insights that Carr gives us to think about.

Choices cannot be made, wisely, unless we equip ourselves with awareness first. Will we choose to further develop habits of Internet use that fragment the mind, reduce our capacity to focus and concentrate, and thereby sabotage our intellectual potential for deep creative and original thinking so essential to address our uncertain present and future?

Carr, ultimately, calls us to value what makes us human. He cites Joseph Weisenbaum, a computer scientist labelled a heretic by artificial intelligence believers, close to 40 years ago, in writing that what makes us human is “what is least computable about us – the connections between our mind and our body, the experiences that shape our memory and our thinking, our capacity for emotion and empathy” [p. 207].

What powerfully resonates with me about the message in The Shallows is how we, as a human species, may be forfeiting the possibility of transforming our consciousness to create a more caring world, unless we question the Internet’s influence upon us.

Nicholas Carr’s hope resides in an anti-Net backlash, a hope reinforced by the large number of responses from “young people.” Carr then points out: “Net culture isn’t youth culture; its mainstream culture.” Provocatively, he adds: “What are Facebook and Google but giant institutions, arms of the new Establishment? What are smartphones if not high-tech leashes?…Some kind of rebellion seems in order” [p. 227].

Humour, as I suggested at the beginning of this post, has a vital role in our lives. In dealing with the serious issue of getting lost in “the shallows,” treat yourself to a chuckle by seeing perhaps your own Internet dilemma mirrored in the hilarious animated short video “What the Internet is Doing to Our Brains.”