When past memories return to one’s consciousness repeatedly through the years, they carry a message. Sometimes it symbolizes the need to tell a story. During my years as a fulltime journalist, my favourite articles to produce were interviews with individuals, some of whom were famous and others under-recognized or forgotten. I recall phoning ornithologist/bird artist Terence M. Shortt, to arrange a visit.

When past memories return to one’s consciousness repeatedly through the years, they carry a message. Sometimes it symbolizes the need to tell a story. During my years as a fulltime journalist, my favourite articles to produce were interviews with individuals, some of whom were famous and others under-recognized or forgotten. I recall phoning ornithologist/bird artist Terence M. Shortt, to arrange a visit.

My intention was to honour his legacy by giving him an opportunity to share his wisdom, based upon a lifetime dedicated to learning about birds, and mentoring other bird enthusiasts. Mr. Shortt invited me to come and sit in his garden, to share the joy that he experienced daily.

One of my lifelong regrets is that I never made it to his garden while Terence Shortt (1910-1986) was alive. I immediately had recognized that his invitation came not just from a gracious willingness to be interviewed. Instead, much more importantly, the enthusiasm so obvious in his voice was his excitement to have an opportunity to share with another person the world of Nature that brought so much beauty and fulfillment into his life.

After confirming the possibility of an interview, I tried to find at least one Canadian magazine that would appreciate such a story – without success. What really angered me was the haughty response from one female magazine editor who sniffed while asking: “What has he done lately?” When I replied that I wanted to do a story on highlights of his life as he saw them and the wisdom that he has acquired, she curtly rejected the story idea. I was infuriated by her arrogance and disrespect, and decided I would visit Mr. Shortt anyway. But, sadly, I delayed arranging a date until it was too late.

Although I denied myself the pleasure of spending time with Mr. Shortt in person – and I hope he benefited instead from the presence of more dependable visitors – here I partially can make amends by acknowledging his legacy, albeit briefly. The fact is, he was a major influence upon the the lives of several living nature artists, such as Robert Bateman. They do acknowledge Shortt’s talents and generosity and have received much more public acclaim than Shortt experienced during his own lifetime.

Important to note about the internet is the reality that it never should be seen as the sole resource to find information. Books and other cultural documents need to be explored, in order to gather more fully insights on the lives and contributions to cultural history of people. Even in recent generations, who knows how many worthy individuals have been virtually overlooked in digital documents.

Ever the intrepid sleuth, regardless, once I identify a scent to follow I am like a hound dog on a trail of pursuit to the sources. I spent most of an afternoon looking up numerous online keywords in order, eventually, to track down any insights at all about Terence Michael Shortt.

He became an acclaimed ornithologist and renown bird artist, almost inadvertently it seems, because his fulltime day job through 46 years was Chief Display Biologist at the Royal Ontario Museum, in Toronto, where he also taught nature drawing. His job did support international trips to study birds elsewhere. Shortt somehow found the time, as well, to illustrate the books of several authors plus compiling his own books to feature his master drawings.

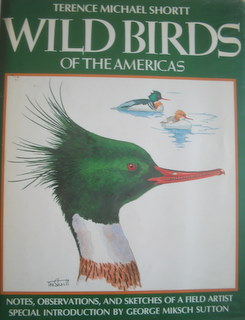

In the production of his own books, about which details are few and far between online, his most popular book (reprinted in different versions) was titled Wild Birds of the Americas (1977), in which his impeccable drawings were accompanied by equally fastidious written observations about his beloved bird subjects. Please note, the cover image shown here probably does not do justice to his palette, which is why seeing original copies of his books is the preferred choice for anyone who can appreciate the significance of colour rendition in book reproductions of original art.

were accompanied by equally fastidious written observations about his beloved bird subjects. Please note, the cover image shown here probably does not do justice to his palette, which is why seeing original copies of his books is the preferred choice for anyone who can appreciate the significance of colour rendition in book reproductions of original art.

Eventually I discovered an August/September 1977 edition of Books in Canada magazine, among its online archived back issues – a genuine gift to Canadian cultural history – in which Shortt’s above-mentioned book is reviewed on pages 34, 35, under “Rails, swans and Shortt takes,” and Shortt himself is interviewed on pages 41, 42, under “Birds fly over the rainbow and Terry Shortt has spent a long, happy life following them.”

Despite several typos, these brief insights offer clues to a uniquely gifted artist and observer of nature, yet unassuming and modest, apparently not interested in being in the limelight. His two-fold passion was to be a witness to the phenomenon of bird life and share whatever he learned with anyone interested.

I wish I had known him, and still kick myself in waiting for another day that never came. Probably each of us can recall someone whom we have overlooked, or perhaps still do neglect. Such individuals could exist within our own families. Also, they could include other individuals who do not seek the limelight yet have given so much to benefit other people, society, the planetary environment and more.

Perhaps such individuals have inner peace that transcends the need ever to be recognized publicly. They might even actively avoid the limelight.

Regardless, intrinsically, we require meaningful interactions in the world around us that enable our soul to feel welcomed. We are social beings who thrive on respectful and genuinely affectionate interrelationships.

Given mainstream society’s obsession with a celebrity culture in our globalized world, I strongly believe we need to give ourselves interludes to reflect on what really matters.

We can strive to restore more balance in a world sorely out-of-balance in regard to whom and what we value, in which daily life for so many people has been reduced to numerous, superficial, fleeting sound bites. I bet each of us probably could identify at least one person, perhaps several individuals, with whom a mutually beneficial experience could unfold by offering the gift of unhurried time spent together.

Each and every generation has something to offer, in order to create a holistic fabric of relationships woven from the continuity of human experience through time and space.

Consider what we are doing to ourselves, collectively, when the authentic wealth of our society is being marginalized, stigmatized and under-valued? What I refer to is the wealth embodied in the knowledge and experience of fellow human beings who have travelled the distance in life to move beyond egotistically assuming they know everything, to discover, eventually, that they know very little. Doing so is the beginning of wisdom.

A recent experience brought to the surface of my consciousness the infamous question put to me so many years ago: What has he done lately? As a creative professional, I just filled in a survey that included a number of questions about how the presence or absence of future royalties would impact on my production of educational work.

But, the survey – typical of various other surveys in recent years distributed to creators – focused only on the past three years. In other words, what have I done lately?

If I have been without paid creative work in that limited period, does that imply that I do not exist, that my voice is silenced from contributing to the wider cultural conversation about societal changes that profoundly affect the livelihoods of present and future creators? Indeed, the 2008 economic downturn severely impacted both veteran and emerging professionals in the creative sector as much as other sectors.

Does not a lifetime of production count? The fact is, I still do receive royalties, albeit modest, both as a writer and a documentary filmmaker, from continuing sales, most importantly educational uses of my previously produced work. Royalties are sorely needed in our current economy in which funding new creative projects is almost impossible. Financing, production methods and marketing all are radically being restructured. (That is why copyright must be respected, to enable royalties.)

Despite my human failings, when I could support myself as a working journalist, I did bring attention to a number of deserving individuals through my published articles and essays. As a filmmaker, my proudest contribution was giving recognition to a remarkable person who was socially, and professionally, marginalized until my documentary shed light on the talents, courage and spiritual tenacity of Everett Soop, in Soop on Wheels.

Who do you know as individuals who expressed generosity and caring to make a difference in the world, yet today might feel isolated and forgotten? Seek out these individuals, and honour them by your affectionate presence and acknowledgment.

Acts of caring are what reinforce our humanity, the most precious gift we bestow on this earth.