I fear what the future holds for younger generations, when so many societal trends appear to be pointing them in a direction away from deep understanding and pathways to develop one’s human potential. Factors include devaluing creative work and higher education in the arts and humanities. The third factor, a society whose cultural and historical foundation continues to be undermined (at least in Canada) by federal government cuts, in which educational institutions now are choosing to undermine the livelihoods of veteran and emerging cultural workers.

I fear what the future holds for younger generations, when so many societal trends appear to be pointing them in a direction away from deep understanding and pathways to develop one’s human potential. Factors include devaluing creative work and higher education in the arts and humanities. The third factor, a society whose cultural and historical foundation continues to be undermined (at least in Canada) by federal government cuts, in which educational institutions now are choosing to undermine the livelihoods of veteran and emerging cultural workers.

I speak from the perspective of a cultural worker, more specifically here as a writer, yet also as a documentary filmmaker.

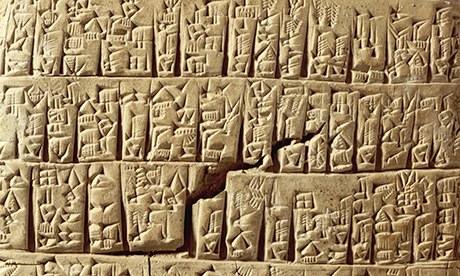

First of all, I want to distinguish `cultural workers’ from `knowledge workers.’ The term `knowledge worker,’ similar to the related term `creative class,’ has been co-opted. It no longer refers to the longstanding societal role of creative thinkers and practitioners who have mapped cultural history since the earliest cultural productions in rock art and clay tablet writings, by our ancestors worldwide.

`Knowledge workers,’ in the online Business Dictionary, refers instead to “data analysts, product developers, planners, programmers, and researchers who are engaged primarily in acquisition, analysis, and manipulation of information as opposed to production of goods or services” – to give the impression that today’s globalized, and digitized, world is somehow more advanced than life lived in real time and real space.

The so-called `knowledge-based economy’ is a lie being fed to the human family by the small number of technological elite, very financially powerful, who want to reduce everyone and everything alive on this planet to consumers, commodities and marketplaces.

Something else is being forfeited in the pursuit of everything technological that reduces all human activity to marketing, particularly when doing so in quick, superficial, and endless, sound and video bites that require as little thinking as possible.

In other words, the challenge that we confront, as a human family, is not only that our social, economic and political lives – not to mention the planet’s environment – are in major transition. But, more importantly, in moving as fast and as superficially as possible, we are losing our moral radar.

as a human family, is not only that our social, economic and political lives – not to mention the planet’s environment – are in major transition. But, more importantly, in moving as fast and as superficially as possible, we are losing our moral radar.

To clarify, `cultural workers’ are thinkers and practitioners in professions which include all forms of media, the arts and education. At their best, the production of images, words and music provoke us beyond mere entertainment to educate us as well.

Cultural production, since the earliest storytellers, requires a huge investment of time and serious intellectual exploration, as well as holistic energy, to help us understand who we are, why history unfolded through particular events, and how we have the potential to evolve into a more caring species.

The best educators who teach in institutions full-time or part-time (some who also are artistic creators) – on salaries, unlike independent cultural workers – use course materials daily. These are based largely upon someone else’s media and art forms of cultural work, whose creation required much research time, deep thought and energy, as well as the well-honed craft of shaping the eventual cultural production, whether written work, film, etc.

The materials used in classrooms can range from cultural productions by the sages of historic times to works by, for example, contemporary writers/researchers, who still are alive and whose livelihoods depend upon the educational purchases of their work, in sales, reprints and royalties.

American author David Korten, founder of YES! Magazine, identifies these cultural workers too, and even includes the field of religion, in his article titled “Are You a Cultural Worker?” In reference to religion, by the way, he refers to those faith institutions willing to undertake transformation that, in turn, speaks to the moral awakening of our time, in which they too can participate “to teach love for all beings.”

Love and respect go hand-in-hand. Love means honouring the contributions of cultural workers who, again, at their best, aspire to life-affirming cultural production, yet most of the time with limited financial assistance as well as eventual limited income. Honouring calls upon users to appreciate creators through decent economic recognition. Respect means cherishing the efforts invested in such cultural contributions.

A recently discovered article titled “The creative class is a lie,” published online in Salon by arts reporter Scott Timberg, October 1, 2011, identifies the essence of what I mentioned earlier, about who benefits from the present knowledge-based society, and who does not:

“… For many computer programmers, corporate executives who oversee social media, and some others who fit the definition of the `creative class’ – … things are good. …

“But for those who deal with ideas, culture and creativity at street level – the working- and middle-classes within the creative class – things are less cheery. Book editors, journalists, video store clerks, musicians, novelists without tenure – they’re among the many groups struggling through the dreary combination of economic slump and Internet reset. The creative class is melting and the story is largely untold.“ [my bold]

The above societal landscape is the back story to what I now want to identify as a key example to illustrate how our society is losing its moral radar – namely, fair dealing. The fact is, the practice of `fair dealing’ is abused and misinterpreted by many users, the abuses now coming as well from educators in post-secondary institutions.

`Fair dealing’ is something that concerns everyone, because everyone uses someone else’s “intellectual property” several times a day, with or without permission. And, yes, the internet offers a lot of content that is freely given by the original creator.

The point is, many folks today take for granted the predominant free culture philosophy as applying to everything on the internet. Creators, meanwhile, keep trying to figure out new ways to monetize some of their respective works available there for that purpose, sometimes giving away selected work as a marketing strategy to sell other work.

Meanwhile, I cannot emphasize enough how the so-called free culture movement is not free at all, but instead has a high cost of destroying freedom of expression by silencing a large number of independent thinkers who gather and make meaning of complex, and controversial, areas of knowledge, in order to raise individual awareness, deepen and broaden understanding across cultures and nation states, in the pursuit of creating a more hopeful world for the larger good.

To illustrate, the latest blow against cultural work in Canada comes from organizations that ought to know better. Yet, therein, resides our societal crisis – a lack of respect exhibited by salaried educators in post-secondary institutions towards independent thinkers and creators whose work these educators are using daily in classrooms.

Such organizations include The Canadian Association of University Teachers (CAUT) and the Canadian Federation of Students (CFS) who announced in December 2013 that they would withdraw their participation from the Post-Secondary Educational Institution Tariff (2011-2013) hearing before the Copyright Board of Canada.

CAUT outlines, in its December bulletin: “Universities and colleges across Canada are opting out of licensing agreements with Access Copyright, relying instead on open access journals, fair dealing, and direct licenses with publishers.”

To add insult to injury, here is an excerpt from the statement by the Canadian Federation of Students: “We will continue this fight on our campuses and in our classrooms until students’ right to use materials for educational purposes takes precedence over private profits.” Unbelievable arrogance is evident here.

When I was a post-secondary student, attaining one arts diploma and three university degrees including a doctorate, I always expected, and happily, to pay for all course materials. Paying the authors of all of our educational materials was the norm – totally acceptable to, and respected by, students. What happened???

Students are endowed not only with rights yet, moreover, with moral responsibilities to pay for course materials, as well as recognize – through citations rather than plagarism – the sources that help them produce their own academic work.

As for the language used in the CAUT bulletin, note the terms such as `licensing agreements’ and `tariffs.’ What CAUT calls tariffs, in fact, are related to the `royalties’ that creators deserve to receive. The reason is that, for most cultural workers (who are not celebrities, yet who could be better acknowledged), their income tends to be modest and intermittent, rather than upscale and steady. Copyright has an essential purpose.

I strongly recommend reading a clearly presented description of `fair dealing’ – as per how it ought to be understood – prepared by The Writers Union of Canada, titled “WHAT IS – AND ISN’T – FAIR DEALING.”

Another excellent resource is iCopyright, for creators, publishers and users, about how to understand copyright. Check out its services. Also see “The Copyright Blog, Valuing Content in a Digital World,” for example, tips for bloggers to protect your content.

Another excellent resource is iCopyright, for creators, publishers and users, about how to understand copyright. Check out its services. Also see “The Copyright Blog, Valuing Content in a Digital World,” for example, tips for bloggers to protect your content.

Important to note is the longstanding fact that educational sales are the major sources of revenue that enable cultural workers to continue their respective creative livelihoods, not just for writers yet, as well, for documentary filmmakers.

As for CAUT, I find two contradictions. First, the organization has spoken out against the federal government cuts to the jobs and research of environmental science and closing libraries. CAUT also criticizes how “Universities sacrifice integrity in pursuing deals” in its December 2013 bulletin, Vol 60, No 10, regarding secret university collaborations with corporate industry and, moreover, restrictions of freedom of expression of academic staff to publish their research findings. These are honourable concerns.

But, at the same time, CAUT does not want to provide economic support to independent cultural workers who raise the types of provocative questions, based on deeply researched knowledge – in course materials for students to develop critical thinking skills – to identify and debate the dangers of particular government policies and increasing corporate influences and controls that limit the engine – freedom of expression – of any authentic democracy.

I am here to spell out, therefore, that the beginning trajectory of educational institutions, now trying to back off from enabling cultural workers to receive royalties as a legitimate and essential form of income, is the tip of the iceberg.

Reneging on such payments would cause a cultural meltdown of enormous human and societal costs, which already are visiting upon the lives of individual cultural workers.

A poverty-level pension based upon an underpaid journalism profession, and reduced royalties in recent years, for example, already is causing me harm in regard to serious poverty and increasing health problems as a consequence. Hence, the long delay in producing this blog post.

Regardless, I felt it important to put a human face on this dilemma. How many hundreds or more of fellow cultural workers are struggling later in life to survive, wishing still to contribute in meaningful ways, yet no longer acknowledged for a lifetime of efforts to make a difference in a troubled world?

How can younger generations even hope for a viable livelihood as cultural workers, if economic reward for their hard work continues to be so difficult to attain? Who will be the storytellers of the future, decently given the financial means to research and document what is happening around us, and to inspire and fuel a transformation of consciousness to become more fully who we can be?

We are witnessing one of the tragic paradoxes of our time, bestowed with the largest bounty of human knowledge through the ages readily accessible to us – that genuinely could enhance the evolution of human consciousness – while the messengers/cultural workers (across all living generations) dedicated to producing it are marginalized, devalued and even silenced.

We all are much more than mere consumers, while some of us also are creators. Let our voices be heard to encourage misguided educators – and students – to appreciate the knowledge content that they study and use. Persuade them to recognize the time, energy and gifts of creative insight, well-informed perspectives and thoughtful practice invested in producing this educational content.

Ultimately, in protecting the livelihoods of cultural workers, we strengthen human civilizations and the hope that, through life long learning and the evolution of our consciousness, we can stand together to heal and co-create a healthier and more peaceful planet that offers dignity to, and compassion for, all beings.

PHOTO CREDIT: Araldo de Luca/Corbis – See above Sumerian tablet in cunieform script, the earliest known type of written language.

POSTSCRIPT: See a two-minute video, posted March 26, offering food for thought – tongue-in-cheek – to value the rights of writers, titled Canadian University Degrees Now Free.

This is excellent Sandy. Might we re-publish?

Thank you, Sandy, for asking permission to republish. Absolutely, yes. In your role as executive director of the Professional Writers Association of Canada (PWAC), I am honoured by your request.

Hi Sandy,

Very nicely analysed. I’ve been engaged in discussion around free culture and fair pay for use of copyright-protected material for well over a decade now. The downward pressure on pricing creative content was around long before digital content and the ease of sharing via the Internet. Writers are, unfortunately, quite used to having to insist on the value of their work to those who wish to use it. We’re used to negotiating at the industrial level, with publishers and other industrial users such as educators.

What’s most disappointing is how one of our industrial partners – education – has positioned itself as somehow NOT an industrial user of content. Millions upon millions of photocopied pages each year, course pack production on a scale that exceeds the publishing activity of many professional Canadian publishers, all claimed for free and without even the respectful interaction of letting the original creators know their work is being used. It’s anti-competitive, anti-cultural and should, in fact, stand in opposition to the very principles of education.

Meanwhile, Canada’s writers continue to visit classrooms and share their knowledge because we continue to believe in those principles. Organizations like CAUT and CFS have failed their members. They have turned away from the challenges of the front-line educators and the students, and sided with bean-counting administrations. It’s shameful.

John Degen, Executive Director

The Writers’ Union of Canada

Thank you, John, for the excellent insight that you provide here and, moreover, for your outstanding advocacy through many years.

I remember, in the early years of my professional writing, how writers had to fight in order to convince the government that writing is a profession, not a hobby. Incredible, eh.

More incredible, today, is the necessity to demand respect to be recognized as professionals – from educators!

What a powerful piece of writing, Sandy. Thanks for pointing me to it, and for sharing your thoughts and insights. This paragraph was the one that hit home for me: “In other words, the challenge that we confront, as a human family, is not only that our social, economic and political lives – not to mention the planet’s environment – are in major transition. But, more importantly, in moving as fast and as superficially as possible, we are losing our moral radar.” Perfectly crafted, unfortunately true. I have shared the post via social media, and hope it brings more readers to your blog.

I appreciate your support Doreen, and recommend my readers browse http://doreenpendgracs.com, to see your writing accomplishments, and generosity in showcasing various writers, plus tips on writing.